Estimating Whitetail Deer Score

August 28th, 2016 by BTC Editor

With the right camera and settings, photos captured can help immensely to accurately gauge a buck’s net score well before it hits the ground.

Hunting stores like Cabela’s have a wide range of trail cameras and filtering through pictures is quickly becoming a favorite past time of hunters. Like Christmas morning, each memory card filled with thousands of pictures is waiting to be opened and scanned. Every hunter will have a different level of “acceptable” target deer to hunt. For rookie hunters, anything that moves will usually suffice. Bow hunters might be interested in the Pope and Young minimum qualifying score as a target buck for the season. For others, it may be that elusive net score of 150 inches(“). And for the seasoned trophy hunters it’s likely to be upwards of 170” (the Boone and Crockett all time net typical minimum). Either way, it depends on what hunting stage the individual is in, where their hunting territory is and perhaps how much time they can afford to dedicate towards hunting season. No matter who you are, where you hunt or what your goals are, Boone and Crockett and Pope and Young conversation clubs established a consistent method of measuring deer antlers many years ago.

Previous to the 1990’s, trail cameras were non-existent. Now a days, it is hard to find a hunter without one. Trail cameras scout 24 hours a day, 7 days a week providing great information regarding:

- herd population

- herd age classes

- frequency of movement

- buck to doe ratio

- target bucks

- largest antlers

- worst genetics

Scoring a deer is the act of adding up all the qualifying inches the buck has. Scoring a live buck is difficult at best as they usually do not stand motionless for long or in the right position to properly gauge their score. This is where trail cameras can really help out, especially models with burst mode that take many pictures in rapid succession. A whitetail deer’s net typical score is composed of 5 components from the antler rack they possess:

- Length

- Height

- Thickness (mass)

- Spread

- Length of abnormal points

Length is measured as the total distance from where the antler start on the head to the tip, referred to as the main beam. If the length of the right main beam is shorter than the left, or vice versa, estimate the shortest. Antler symmetry is a factor, so an official score sheet will add the actual length of both sides and subtract the difference. Therefore, starting with the shorter main beam eliminates the step of adding and subtracting the inches that are not present on both main beams. To get a good estimate of length you need a picture of the buck from the front (looking at the camera) or top (facing the camera head on, but sniffing the ground). This orientation clearly outlines the main beam, how far it goes out towards/past the ears and will also help identify the shorter one (if any). A helpful second picture is a side profile of the deer’s head on alert (head up). This gives great indication of how far past the nose the main beam goes. The distance from the eyes to the tip of the nose on a mature buck in Alberta is 7”. Visit some mounted deer from your local hunting area and take measurements of this same distance and use it as a reference point. At the end you should have one number – the length of the shortest main beam.

Using the outer distance between the eyes atop the skull as a gauge (6”), I estimated each main beam to extend outwardly 7.5” and then turn back inward 6.5”. Photo also give a clear view of the spread estimated at 19” (6.5 + 6 + 6.5) using the same gauge. Excellent photo to show the difference in the first tine set (G1’s) and to confirm this buck is a 4×4. I estimated the shortest G1 tine at 4”, again with the same gauge.

Using the distance from the eye to the snout tip as a gauge (7”), I estimated the middle part of the main beam to be 8”. I also used this picture (and same gauge) to estimate the second tine (G2) at 9”and the third tine (G3) at 7”. Estimated total tine height is 20.5” (9” + 7.5” + 4”). The main beams look very symmetrical but I estimated the right one at 22” (7.5” + 6.5” + 8”).

Net typical height is the total length of all tines (points) that come off the main beam, minus any differences between the sets. To begin, choose the first tine (starting from the head) sprouting from each main beam and estimate the length of the shortest one. Then use the same process on the next set of tines, until you are done. If one main beam has more tines than the other, ignore the extra tines. Only measure the typical tines, meaning where you’d expect the buck to have a tine coming off the main beam. You will need as many pictures as possible with the buck looking in all directions with his head held high. Use a reference like the distance from the eye to the tip of the nose to gauge the length of each tine. In the end you should have one number created by adding the estimated length of the shortest tine in each set. For example, if it was a 5×4 typical buck, you would have: (Shortest G1(brow) tine) + (Shortest G2 tine) + (Shortest G3 tine) + 0. Note: The tip of each main beam is not a tine and was already accounted for when estimating the main beam length. Official scoresheets have an excellent visual representation of the tines and their common names (G#).

Photo gives a good indication of how many tines are on the antlers. In this case, an even three per side.

Mass (or thickness) of each antler is measured before each tine sprouts until you reach four measurements. Add those four number together for total mass. Again, use the antler that looks to be the smallest. More often than not I don’t bother with estimating this measurement and just use 18” on mature deer as a baseline. If the deer antlers look really thick, I will add up to 3” and vice versa for skinny antlers. Be cautious of bucks that move during photo capture causing them to appear ‘heavier’ (more mass) than they actually are. Browning trail cameras shoot the fastest shutter speed (even at night), minimizing motion blur and provided crisp photos to estimate mass. I have used both the snout and eye socket as a reference to diameter of the main beam because they both measure around 1.5 – 2”, but like I said, I usually just go with 18” as a conservative estimate.

Unabstracted view of main beam thickness against grass, however this deer is in velvet (which counts). Compare it to the eyeball and snout.

Excellent photo to show symmetry because tine sets. This deer appears to have the same tine length on both the right and left antler.

Spread is the width between the left and right antler. Spread is measured by finding the longest distance between the inside of the right and left main beam. Unlike length, mass and height, spread is only counted once, not twice (for each antler side), therefore it contributes the least towards final score. A really wide 4×4 buck will be most impressive at first glance, but a narrower 5×5 buck should have a better score because it’s far easier to have 8 additional inches by having a forth 4” tine on each side as opposed to 8” between the right and left antler. A picture showing the ears and the buck looking at the camera is great to estimate spread. I have also used the skull as a good gauge to estimate spread.

Once you have estimated length, height, mass and spread, the final number required is the total length of all abnormal points. Any picture you have will help find these hidden deductions. Estimate the length of each one and tally them up to one number for both the right and left antler. If you have more than 15” of abnormal points, it qualifies for non-typical scoring instead of typical scoring.

For your final estimated net score do the following:

- Length + Height + Mass

- Double it

- Add Spread

- Subtract length of abnormal points (if less than 15 otherwise add)

The burst mode on this Browning trail camera took 8 pictures of this buck in rapid succession, providing various camera angles to accurately estimate the buck net typical score at 140”. ([22(length) + 20.5(height) + 18(mass)] x 2 + 19(spread) – 0(non-typical deductions)). I never did shoot this buck, so I’ll never know fore sure though.

An official score sheet is much more precise when it comes to deductions but since estimating the shorter and smaller side of the antlers eliminates those differences (from non-symmetry) immediately.

Remember, score is just a number, it does not consider effort, method of hunting, determination or atmosphere which all contribute to making a deer hunt memorable. Trail cameras are an excellent tool for estimating buck scores before a hunter decides to target that particular deer. I know I still enjoy “if it’s brown it’s down” hunts but I have enjoyed holding out for specific bucks captured on trail cameras that I know will qualify for Pope and Young records book based on the estimating process described above.

By Gord Nuttall

Gord Nuttall is an enthusiastic outdoorsmen and award-winning freelance writer that spends countless hours sorting through Browning trail camera pictures of western big game animals to pursue. Follow all his adventures at www.facebook.com/prostaffgordn

Nighttime Trail Camera Images – Putting Light On The Subject

August 15th, 2016 by BTC Editor

The evolution of the trail camera has been simply remarkable over the last several years, from taking 35mm film to the photo shop to the almost instant gratification of looking at them on your phone, things are simply in a place that was once only a dream.

With that said, there are still some factors in play when it comes to nighttime images that make them seem behind the times. With all of the advances in technology, why have nighttime images not been perfected yet? Well, in this format, we’ll do our best to explain the basic science of nighttime images on trail cameras.

Seeing the Waves

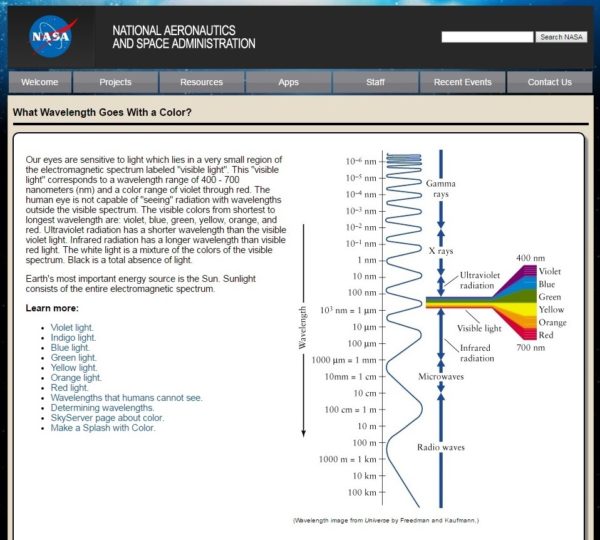

Nope. We’re not at the beach. But to develop a basic understanding of what’s going on with nighttime images you will want to make sense of the following to help differentiate between the various types of flashes:

- Our eyes can only see light that exists within a small range of the electromagnetic spectrum.

- That electromagnetic spectrum is measured in wavelengths.

- Those wavelengths are measured in nanometers.

Ultimately, these nanometers are your take away from this section because this is the measurement that you can use to understand how each type of flash impacts the quality of your game camera pictures.

If you need a visual aide to help you more effectively wrap your head around the concept of nanometers, NASA has created a handy below:

SOURCE: http://science-edu.larc.nasa.gov/EDDOCS/Wavelengths_for_Colors.html

Measuring the Flash?

Well, we’ve given you the basics on nanometers, but now you’re asking: why do I care? Well, we’ll do our best to explain that here as simply as possible across all three types of flashes found on trail cameras:

White Flash Cameras

If you look at the chart from NASA, you will see that they define “visible light” as being in the range of 400nm to 700nm. That’s pretty much what you get with a “white flash” camera and that’s how you get to see the full color images.

SOURCE: http://www.trailcampro.com/collections/shop-trail-cameras/products/reconyx-hyperfire-hc550

Low-Glow/Standard Infrared (IR) Flash

Now it starts to get a little more complex, because we’re going to step outside the range of “visible light” and move into the infrared range. For cameras that fall into the “low-glow” or “standard” infrared (IR) category, it’s reasonable to suggest that most of these cameras measure around 850 nanometers.

Now, even though these camera flashes technically fall in the “Infrared” category, they are still close enough to the red in the “visible light” range that (A) if someone is looking in the general direction of the LED bulbs when it takes a nighttime image they will see a “low red glow” and (B) the flash still generates enough illumination to take a reasonably good nighttime images.

Obviously, you sacrifice the color of the images here since you are using a flash outside of the spectrum found in the “visible light” range, but you are still getting a reasonably crisp image without the “flash of lightning” effect you get with a white flash camera.

Invisble/No Glow/Black Flash

As we discuss this type of flash, it is worth noting that it still falls within the infrared light range. It is simply further away from the “visible light” range than the low-glow infrared flash cameras. With flashes in this category, it is reasonable to assume that most of them can be measured around 950 nanometers.

The net result of this is that the LED bulbs are not visible when taking a nighttime image, BUT in exchange for that “invisibility” you are sacrificing image quality when compared to the other types of flashes. This is because invisible flash cameras simply do not illuminate the subject matter as much as the other two.

In this image below, if you look back up to the one we used for the “low-glow” images you’ll notice that the image captured by the “invisible flash” camera is a little grainier and has a little more “white noise.” They are both still good images, but you can see that one is a little clearer than the other.

Speed Matters

Now, we could get into a long dissertation about the impact that SHUTTER SPEED has on trail camera images, but for today we’ll just provide you with a few quick notes and save the essay on “shutter speeds” for another day.

In this context we only want to relate shutter speed to the amount of light that is available for capturing images. So here goes: the more light you have available, the faster the shutter speed can be. The less light/illumination you have available, the slower the shutter speed must be.

Basically that means this: during the day you have enough light for the shutter speeds to be super-fast and capture cool images of deer jumping and birds flying. This is why most of the cool action shots we see in trail cam pics are daytime pics.

It also means that as you move further away for the visible light range with your flash (i.e From 700 nanometers to 850 nanometers to 950 nanometers…), the shutter speed must slow down to allow enough light inside the camera to capture nighttime photos. In layman’s terms, as you move from a white flash to a low glow IR flash to an invisible flash, you are increasing the likelihood of blurred images because the shutter speeds needs to slow down. While this example isn’t horribly blurred, it still demonstrates that the illumination from an invisible flash camera accompanied by the slower shutter speed, doesn’t always give you the cleanest image in the world.

What Do I Really Need to Remember?

Well, here is the gist of it, starting with the very basic premise that there are two types of trail camera pictures: daytime pictures and nighttime pictures.

Beyond that, based simply on game cameras, there are 3 types of nighttime images: those taken with a white flash, those taken with a standard/low-glow IR flash, and those taken with an invisible/black flash.

So if we take those four types of images and rank them based on potential quality of the images based on the lighting, they would be ranked as follows:

- Daytime Images

- White Flash Images

- Low Glow/Standard IR Images

- Invisible/Black Flash Images

Obviously, there can be a lot more depth to the discussion on flashes and nanometers and shutter speeds and everything else that leads to the trail camera pictures you find on your SD cards, but hopefully this gives you a little bit more of a foundation for understanding why some of the pictures you find on your SD cards look the way they do and helps you with you game planning when it comes to where you put your different types of trail cameras!

Tom Rainey

Tom Rainey has been with Browning Trail Cameras ever since they were introduced at retail and enjoys hunting everything from squirrels to whitetail deer…but his obsession is turkey hunting. His grandfather purchased him a Belgium Browning 20-Gauge A-5 prior to his birth and he has been a fan of the Browning brand ever since…